Five years after it began in London, the historic “David Bowie Is” exhibit makes its last stop at the Brooklyn Museum, where it runs from March 2nd to June 15th. It’s a stunning tour of Bowie‘s world – whatever your level of Bowie fascination, it’s impossible to walk more than a few inches without being dazzled. It has previously unseen relics from all over his 50-year career, from his collection of designer shoes to his Seventies coke spoon, labeled bluntly, “Cocaine spoon, 1976.” As Bowie intended, the exhibit began in London and ends in New York, as his life and career did. For the man who sang “My brain hurt like a warehouse” in “Five Years,” it’s not just a collection of his artifacts – it’s a collection of all the different people he was.

When “David Bowie Is” opened at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the rock legend had just shocked everyone by coming out of retirement with a new album, The Next Day. As the exhibit has toured the world, it has kept growing. In Brooklyn it’s more massive than ever: stage costumes, drawings, handwritten lyrical drafts, sketches, gig posters, video footage, right up to his notebooks for Blackstar, when he was working at warp speed to beat what he knew would be the final curtain. He lived just long enough to release Blackstar on his 69th birthday, two days before he died from cancer, making “David Bowie Is” an intensely emotional tribute to an artist who kept creating and changing to the end.

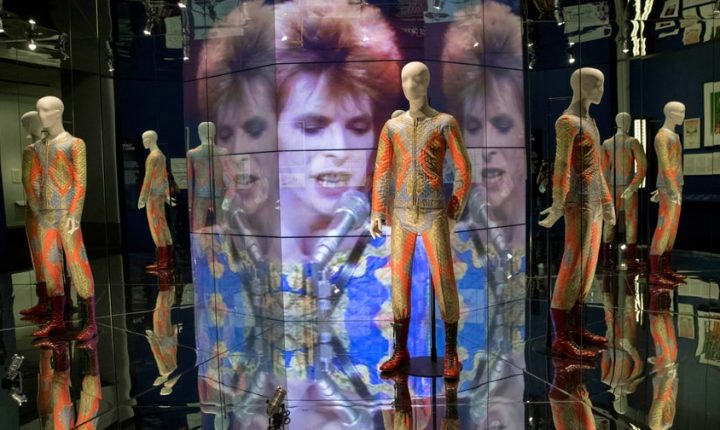

Considering his level of deranged debauchery in the 1970s, it’s amazing this Cracked Actor managed to hang on to any of these things – seeing his Berlin apartment keys, from the time he lived there with Iggy Pop, makes you marvel he ever knew where his keys were. But “David Bowie Is” reaches back to his London childhood, with a photo of Little Richard he’d treasured since the Fifties. And as you’d expect, there’s plenty of fantastic clothes – like his billowing “Tokyo Pop” suit, designed by Kansai Yamamoto in the early 1970s for the Aladdin Sane tour. Bowie described the suit as “everything I wanted … outrageous, provocative and unbelievably hot to wear under the lights.”

There’s something fitting about presenting Bowie’s life story as a vault full of artifacts, since he was an artist who always defined himself as a fan first and foremost. As he explains in a BBC interview heard in the exhibit, “I wanted to be thought of as someone who was very much a trendy person, rather than a trend.” He might be the only rock star who ever aspired to be seen as “trendy” – but as Bowie never tired of explaining, he saw himself as a creature of his book, record and art collections. As he recalls at one point, recalling his teenage devotion to jazz albums, “I was convinced I was an Eric Dolphy fan. So I would listen to the damn things until I became an Eric Dolphy fan.”

The exhibit emphasizes Bowie’s onstage performance – there isn’t much in the way of musical gear or instruments. There’s his copy of The Oxford Companion to Music, the book he used to teach himself musical notation when writing parts for his debut album. There’s also a legendary piece of hardware that has left a permanent mark on Bowie fans’ brains – the EMS AKS briefcase synthesizer that Brian Eno used on the trilogy of Low, Heroes and Lodger, with its knobs, dials and joystick. Eno gave it to Bowie in 1999 with a note: “Look after it. Patch it up in strange ways – it’s surprising that it can still make noises that nothing else can make.” Bowie ended up using it on his next album, Heathen.

There’s a Western Union telefax he received from Elvis Presley in 1976: “Wishing you the best in your current tour. Sincerely, Elvis and the Colonel.” The typed transcript of his famous 1974 Rolling Stone interview with William Burroughs. A doodle from John Lennon, inscribed, “For Video Dave, with love.” “David Bowie Is” barely alludes to the man’s private life, beyond a Warhol-style 1994 lithograph of his wife Iman. As for Andy Warhol himself, that friendship was never meant to be. The exhibit includes rare film footage of Bowie’s visit to the Factory in September 1971 – the only time Warhol and Bowie ever met, strange as that seems. It’s a painfully awkward meeting – Bowie eager to please, trying a bit too hard (“I look like Lauren Bacall, I think”) while Warhol chews gum behind his shades, not at all flattered by Bowie’s tribute song and dropping hints about how hard it is to get work done when he’s interrupted by visitors.

Some of the most poignant artifacts are tantalizing diary entires, like the January 1975 moment when he gushes after recording his future Number One hit “Fame.” Bowie had spent months trying to lure his new friend John Lennon into a recording studio – “Fame” was the result. As Bowie writes in the diary, “Some wonderful publishing is Fame. My first co-written with Lennon, a beatle, about my future.” A few lines down, he notes, “Am happy.” (What’s weirder – Bowie feeling the need to remind his diary who Lennon is or his reluctance to capitalize “Beatle”?) A year later, in the chemical haze of January 1976, Bowie is writing himself a pep talk: “The lady did not. I’m very of the ‘I can.'” There’s a handwritten lyric sheet for “Win,” dated December 1974, with the punch line “All you’ve got to do is Win!” Bowie draws the exclamation point as a lightning bolt, which is touchingly boyish in itself.

And over and over, there is fashion, with a parade of costumes that hardly anyone else on earth could have worn. There are his sleek suits from his 1976 Station to Station tour and the film The Man Who Fell To Earth, designed by Ola Hudson – later known to the rock world as Slash’s mom. Since Bowie always admitted he couldn’t remember a thing about making Station to Station, it’s revelatory to see his stage designs and lyrical notes, as he threw himself into the sinister character of the Thin White Duke, who he described as “ice masquerading as fire.” There’s an early draft of the title song, with lyrics he cut: “You look like a bomb/You smell like a ghost/You eat like a terminal girl.” A consistent theme of Bowie’s shoe collection: He really knew how to work platforms, making sure he always got a proper boost off the ground. Just one of the many tricks he learned from that Little Richard photo.

So many clothes, so many lives, so many Bowies. There’s his turquoise suit from the “Life on Mars?” video, designed by Freddie Buretti to be filmed by Mick Rock – a suit Bowie wore only once, but to unforgettable effect. There’s his Pierrot clown suit from the “Ashes to Ashes” video. And a tissue blotted with his lipstick from 1974, retrieved from the pocket of an old suit. “David Bowie Is” doesn’t merely show off these artifacts – instead, the exhibit brings them together to build an immersive narrative. It tells one of the strangest and most inspiring of modern stories. As the man once sang, such is the stuff from where dreams are woven.